“Out of these animals, which has more sex: the elephant, gorilla, cat, rabbit or honey possum?” asks Mechai Viravaidya.

Posing the question from his office in Bangkok, the octogenarian explains how, over almost 50 years, he has used humour to tackle serious and sometimes taboo topics in an attempt to address the serious issue of birth control.

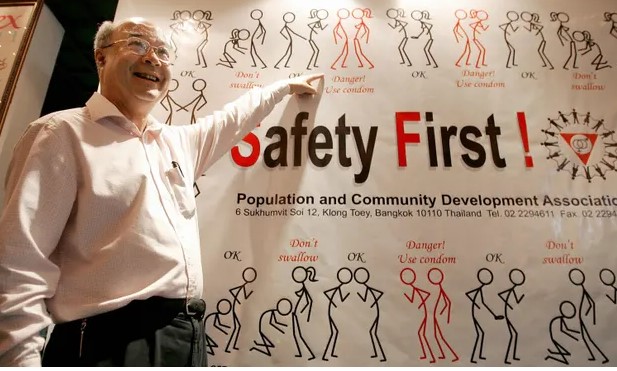

That’s why he is known as Thailand’s “Condom King”.

From hosting vasectomy festivals to condom-blowing competitions and using sheaths as shoe shine, the activist has become a national treasure through his work on destigmatising contraception in a historically conservative culture.

“We came up with a new alphabet. [We used] B for birth, C for condom, I for IUD [intrauterine device], V for vasectomy,” Viravaidya says. But it was the condom that seemed to resonate the most, and so it became central to his family planning work.

Born to a Scottish mother and Thai father, Viravaidya studied in Australia before returning to Thailand in the 1960s where a job in economics at a governmental agency showed him how high population growth was contributing to rural poverty.

In the 1960s, the average woman in Thailand gave birth to six children and population growth stood at 3%.

Establishing an NGO called the Population & Community Development Association (PDA) in 1974, Viravaidya’s team began promoting family planning – recruiting neighbourhood residents to share key information as well as contraceptives.

He then opened a string of restaurants aptly named Cabbages and Condoms as well as the Birds and Bees Resort, to fund the foundation.

There were initially pockets of resistance, Viravaidya says, with some suspecting the work would “corrupt the youth”. And when PDA began campaigning for condom use to tackle the Aids epidemic in the 1980s, some thought it would make people “more susceptible to early sex”, he says.

But taking no as a question rather than an answer and using humour helped break down the barriers, Viravaidya says. “When people laugh together, it’s very hard to hate.”

In the decades since, population growth has dropped to 0.3% and the average family now has two children and poverty levels have decreased to 6.8% as of 2020. The country also saw a 90% decline in new HIV infections from 1991 to 2003.

Viravaidya has gone on to hold multiple governmental roles and acted as a UN Aids ambassador, as part of a résumé that lists him as a Time magazine “Asian hero”, and an awardee of the UN gold peace medal and the Bill and Melinda Gates award for global health, among others.

Gates himself named Viravaidya as one of his “heroes in the field”, stating that his “extraordinary life and work in global health and development has helped improve the lives of millions of people in Thailand”.

Yet, at 81, Viravaidya says his work isn’t done. A lack of sex education in schools, he says, is contributing to a high number of births among teenagers today – in 2019, 23 births out of every 1,000 were by adolescents – while poverty and food insecurity persist in some areas.

The answer, he believes, lies in using schools as a “platform for changing lives” and letting the initiatives be driven by those they’re trying to help.

“These are the allies that are terribly important,” he says, explaining that 49 years ago PDA trained 320,000 rural school teachers in how to integrate family planning into lessons. “You can just say that, in arithmetic, if a farmer has 10 children [and] 10 acres, how many acres per child?”

Today, Viravaidya’s method sees students teaching each other sex education in schools across the country, including in the Mechai Pattana bamboo school, which he established in the north-eastern province of Buriram in 2008.

The flagship school gives students a leadership role and aims to teach empathy and compassion while empowering them to improve the economic development of their villages.

There’s a mandated one day a month in a wheelchair for all students, phones are banned except for an hour a week and a meal is missed once a week in order to experience hunger.

“The emphasis is to have good citizens who are honest, who share, who respect the rights of other people, not just gender, but every element of trust, and also to be able to find answers and not give up, to have grit,” he says.

Viravaidya’s only regret, he says, is that he didn’t start the school initiative earlier. And the answer to the question? The honey possum who, he explains, as popular prey, “has to have sex all the time”.