Vietnam’s brutal acid attack epidemic. Tran Thi Ngoc Dep had only been working at a Can Tho seafood factory for two months when a splash of liquid hit her in the face.

It was a dry afternoon in November.

Dep had just turned 17 and thought a couple of boys from the factory had playfully splashed her with a bottle of water.

Then the liquid began to burn.

At Can Tho General Hospital doctors sent Dep to specialists at Cho Ray in Ho Chi Minh City who could treat the third degree burns that covered her face and her neck.

Dep lost an ear and vision in one eye.

“My sister is a straightforward and friendly girl, and she was very pretty, too,” said her younger sister Xinh, who quit work as a hairdresser in Saigon to make sure Dep is well cared for as she undergoes treatment at the biggest public hospital in southern Vietnam.

On a recent afternoon, Xinh pulls out her phone and points to a young girl wearing a sleeveless black shirt, her long black hair pulled back to reveal a broad smile.

“There were a lot of guys chasing her,” Xinh added, “but my sister wanted to take her time and stay friends with them.”

By the time Dep had endured her fourth skin graft, police had identified her assailants. It was not an act of jealousy, but a revenge attack orchestrated by a roommate’s ex-boyfriend, who suspected Dep had something to do with their breakup.

“HE WAS A CLOSE FRIEND, THEY USUALLY CHATTED ON FACEBOOK,” SAID XINH, WHILE DEP LAY SILENT ON THE SINGLE WHITE SHEET STRETCHED OVER HER HOSPITAL BED.

The girls’ grandfather gave them both names that translate as “beautiful”, but doctors have had to shave Dep’s long hair. Her porcelain pink cheeks have melted into layers of red scars. “Things happened so quickly, we are still in shock,” said Xinh.

Dep is the latest acid attack victim to seek treatment at Cho Ray Hospital. Dr. Ngo Duc Hiep, head of the Burn and Reconstructive Surgery Unit, has been treating her for a month.

Acid attack victims account for two to three percent of the patients he sees every year.

“Around 40 to 60 cases,” he estimated.

Official statistics on acid attacks in the country are hard to record. While the issue in Asian countries like Cambodia, India and Pakistan is constantly mornitored by domestic and transnational organizations, the situation in Vietnam is rather off the radar.

The violence was mentioned in a report of “Violence against Women in Vietnam” by the World Organization Against Torture (OMCT) published back in 2001, when it also quoted the number of acid burn victims treated in Cho Ray Hospital as 114 between 1994 and June 1997.

However, according to an OMCT representative in an email to VnExpress International, the study has not been updated since then due to lack of funding.

Victim blaming

Unlike most South Asian countries, Vietnam’s acid attacks rarely relate to so-called “honor crimes”, or assaults on women who have “dishonored” their families.

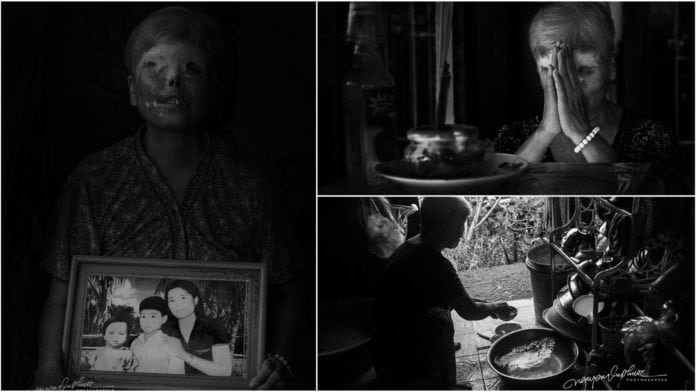

“They sometimes arise out of a burst of anger from a simmering spat, suspicions of an affair, or gang violence,” said Nguyen Vu Phuoc, a photographer who has spent three years tracking acid crimes for one of his ongoing photo projects.

His work gained international attention last July after he posted part of his series, entitled “More brutal than death – Reality of acid burn victims in Vietnam,” on Bored Panda — an art and content-sharing site.

Phuoc maintains a database of acid attacks gleaned from media reports. He hopes to reach out to every victim.

Although most of the victims are female, Phuoc recorded several cases in which men were targeted. The causes range from gang turf wars to run-ins with debt collectors and violent neighbors.

“Whatever background they were from, all of the victims end up being pushed out of their communities or isolating themselves from the rest of the world,” he said.

“I OFTEN FIND THE VICTIMS ARE BLAMED FOR THEIR WOUNDS,” VU PHUOC SAID.

“When people encounter a face scarred by acid, many tend to think he or she must have done something morally wrong to deserve such a harsh punishment — cheating on their spouse, or wrecking someone else’s happy home.”

The 50-year-old photographer attributed the prejudice to the history of an infamous acid attack in 1961.

–

The victim was a Saigon club dancer named Cam Nhung who’d become entangled with a married colonel in the Ngo Dinh Diem regime. By the time the colonel’s wife was found guilty of the assault, the incident had captured the city’s imagination as “a classic example of acid violence”.

Years later, a photo reportedly of Cam Nhung emerged, showing an old woman with her facial features completely wiped out, sitting with a small picture of the dancer in the heyday, begging for food on the street.

The story continues to cast a long shadow on victims today.

“The popular presumption that the scars attest to some wrongdoing pushes survivors deeper into isolation and desperation,” said Phuoc. “Everyone I’ve photographed has their own story, but they all struggle with feelings of inadequacy and a lack of self-worth; it’s not easy for them to open up.”

The legal fight

A month into her treatment, Dep was visited by Hoang Tang Thi Thu Huong, another acid survivor.

Huong’s incident made headlines in 2016, after the 21-year-old student was squirted with the noxious-substance in the middle of a crowded street in Go Vap District.

Huong’s assault stemmed from some conflicts with her ex-roommate, Luong Thuy Kieu Quyen, who later organized the acid attack with her boyfriend. Quyen later told police the whole scheme only cost her a million dong ($44).

Acid consumed fifty seven percent of Huong’s body. The liquid ate through most of her nose and left her blind in one eye.

Splashings

“I’ve heard of acid splashings before, but the stories always sounded like something far away,” Huong said in a video interview, “like they are only bold acts of revenge for extramarital affairs or something. I never thought it would happen to me.”

Quyen was later sentenced to seven years in jail. Last September, Huong successfully appealed the decision and had it extended to nine and a half years.

“I just want to send a clear message to anyone who has any notion about using that deadly substance on another human being,” Huong said.

Legally, acid violence offenders in Vietnam can be given life in prison or even death sentences. Yet in most cases, the culprits rarely see more than a decade in prison.

“Acid crimes have been classified as first-degree murder in Vietnam’s Penal Code,” said Do Hai Binh, a lawyer in Ho Chi Minh City. “But in reality, if the victims survive (as is so often the case) the perpetrators escape the maximum penalty.”

Binh has represented several acid victims and has seen cases where acid assailants hit a crowd of up to five people and escaped death.

“There is a loophole in the law,” he said. “We cannot expect to deter future attacks.”

Acid restriction debate

With her attackers now in jail, Huong believes more can be done to prevent further assaults.

“I keep thinking about the person who sold my attackers a bottle of acid,” she said. “It could have been different for me if they had said no.”

Huong’s attack stirred a debate about clamping down on the corrosive chemicals now widely available on the streets of Ho Chi Minh City. At Kim Bien Market in District 5, the price of a bottle of acid ranges from as low as VND10,000 to VND45,000 ($0.44 to $1.98).

Binh, the lawyer, also thinks licensing sulphuric acid vendors will help prevent abuse.

“The law holds you accountable if you rent your car or motorbike to somebody considered unabe to drive and who later causes an accident. Why can’t we do the same to anyone who sells acid or helps attackers buy it?”

Others have voiced concerns about tightening regulations.

“We should be cautious here about imposing restrictions on the sale of acid,” said Vu Phi Long, former Deputy Chief Justice of the Ho Chi Minh City People’s Court. “It could violate the freedom of commerce, since acid is widely used in metal processing, bleaching or the production of batteries.”

Long likened acid to knives and hammers. “As dangerous as acid can be, it still depends on the people who use it. Those determined to turn it into a weapon can just extract sulfuric acid from everyday batteries.”

The survivors

While the nation struggles to develop a strategy to prevent further attacks, the survivors are focusing on tomorrow.

Huong always takes care to describe herself as “in better shape” than most acid survivors. Stories about her case generated a huge response on social media and Huong received an unprecedented outpouring of sympathy and financial donations.

A Korean plastic surgery clinic in Saigon picked up her case and offered Huong free reconstructive surgery.

Others not so lucky

But many others haven’t fared as well.

Dr. Hiep at Cho Ray Hospital said most of his patients and their attackers are poor and uneducated.

As a doctor, Hiep sometimes finds himself seeking financial assistance for his patients, including Dep, mostly from individual philanthropists.

“I’ve never heard of a case in which the court has ordered compensation from the attacker to help cover even a small fragment of the medical bills,” he said.

“There is no organization or association whatsoever working on this particular issue,” said Dr. Ngo Duc Hiep.

The average patient heals in one or two months, but rehabilitation from such an attack can take a lifetime.

Hiep, who is a dermatologist, frequently has to play the part of a psychotherapist for the victims and their families. “We don’t have therapists or counsellors for acid survivors, even though this kind of assault is very traumatic. Patients are always in shock and many lose the will to live.”

When Huong began to visit other acid survivors between surgeries, she came to realize there has never been a concerted effort to support them, financially, medically, legally or psychologically.

Many victims reach out to Huong, mostly seeking solace.

“I don’t know how to help them, to be honest,” Huong said. “I can only tell them to persevere; that they are not alone. Most of the time, we just sit and cry with one another.”

Nhung Nguyen – VNExpress

–

You can follow BangkokJack on Instagram, Twitter & Reddit. Or join the free mailing list (top right)

Please help us continue to bring the REAL NEWS – PayPal